Did you publish in a top-top journal?

Journal impact factors are a cheap heuristic for assessing individual manuscripts or authors

“That’s good work”, a senior scholar commented publicly during one of my first-ever academic evaluations, “but why didn’t it appear in the top-top journals of the discipline?”. He went on to list the three journals with the highest Web-of-Science impact factors in political science. Below that nothing noteworthy seemed to exist.

Honestly, this somewhat dismissive comment bugged me a bit at the time. After all I was lucky enough to have gotten my first papers into those journals that I read myself (and that happened to rank in the top-10 by the IF measure the evaluator seems to resort to). They also had started to collect quite a few citations by other scholars whose work I admired. But apparently that wasn’t “top-top” enough.

In later academic evaluation processes (sometimes also sitting on the other side of the table), I observed that this simple heuristic usually pops up very quickly – the work of a researcher, of groups or projects, or even of whole institutes is assessed by whether their work was in the top-3 or sometimes top-5 impact factor journals on whatever disciplinary list was considered most suitable.

This heuristic irritates me time and again. To be sure, I agree that publishing and influencing debates are key criteria for scholarly success. But even without getting started on the usual complaints about erratic review processes, potential Zeitgeist-biases, and varying audience sizes, narrowing the benchmark to a very few selected outlets and especially the inference from aggregated impact factors to individual manuscripts or authors continues to annoy me.

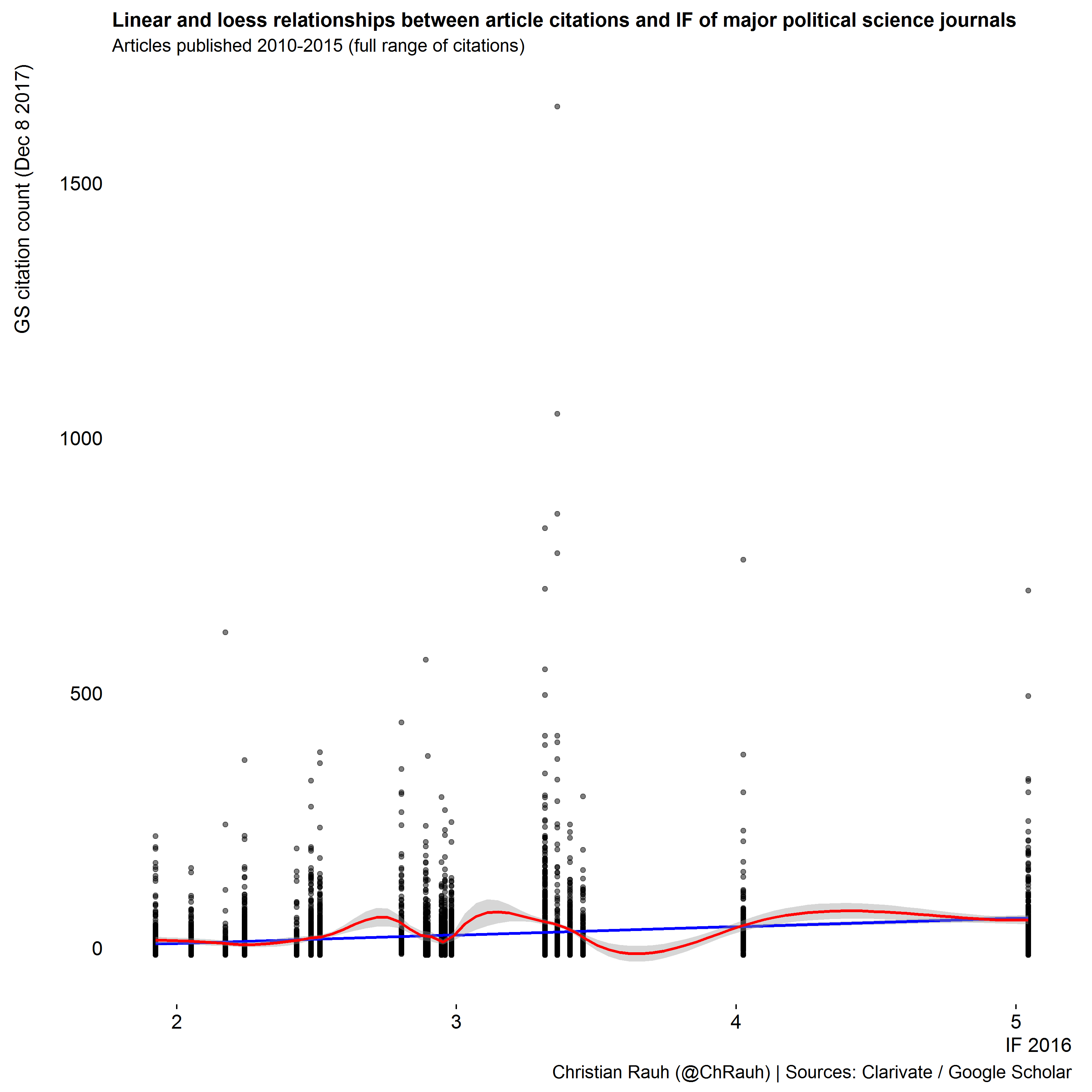

This hold in particular when this heuristic is pushed by quantitatively well-versed colleagues. Journal impact factors, after all, represent average values. And we hardly would get a paper published in a “top-top” journal if it would just draw inferences by looking at averages only. Averages are very sensitive to outliers and we usually would ask for more information about the underlying distribution – e.g. the standard deviation around the observed average. And we would be particularly skeptical about using the average as a comparative benchmark or the basis for inference when dealing with non-symmetric (=skewed) data distributions.

But rare outliers, large standard deviations, and skewed distributions is exactly what one would expect from the citation counts that make up journal impact factors: Amongst other things, we know about the prevalence of name-recognition dynamics and “Matthew effects” in scientific publishing for a long time (Merton 1968).

Under these conditions the citation averages that impact factors represent are hardly informative for comparing journals and especially for drawing inferences about individual manuscripts within these journals.

Distributions of citation counts

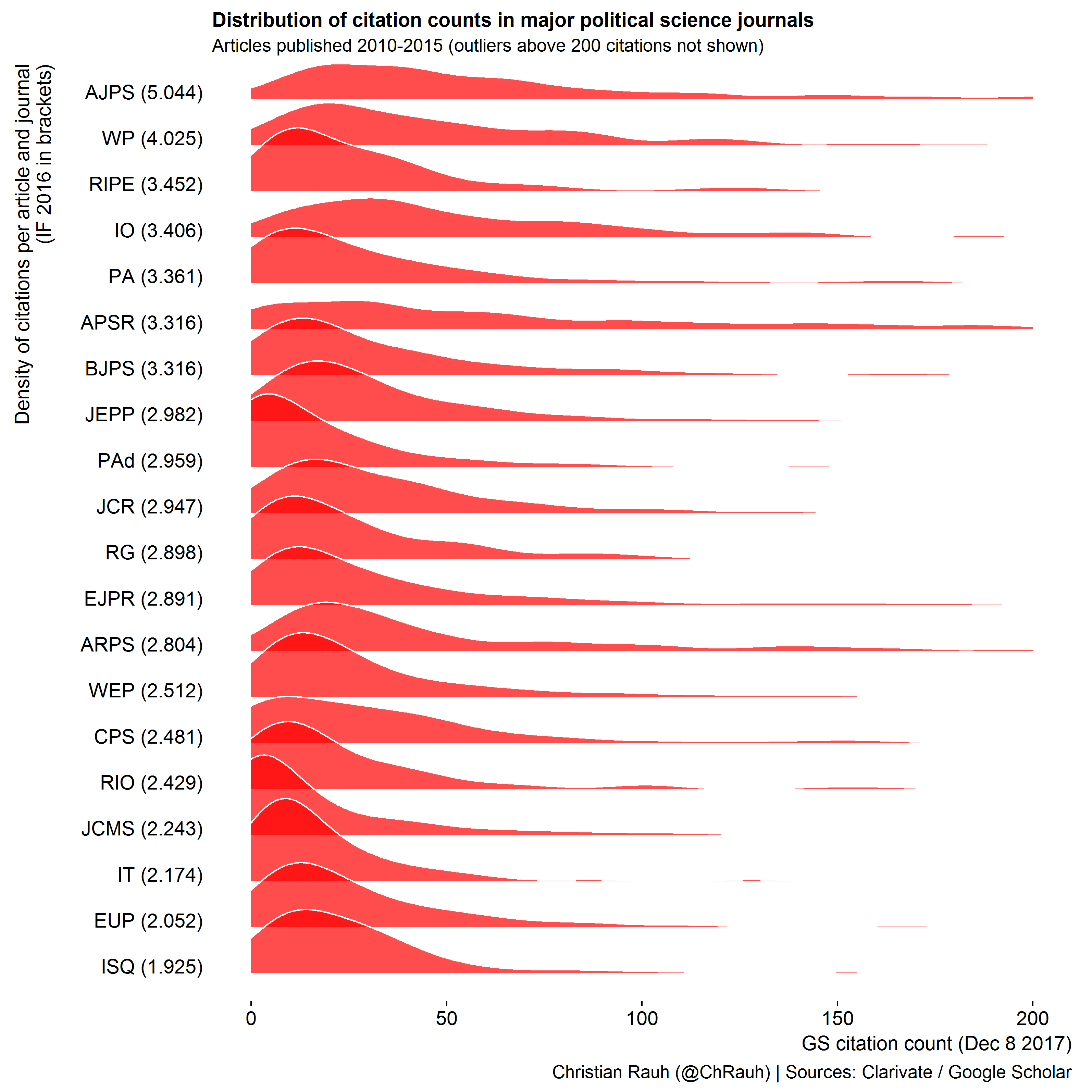

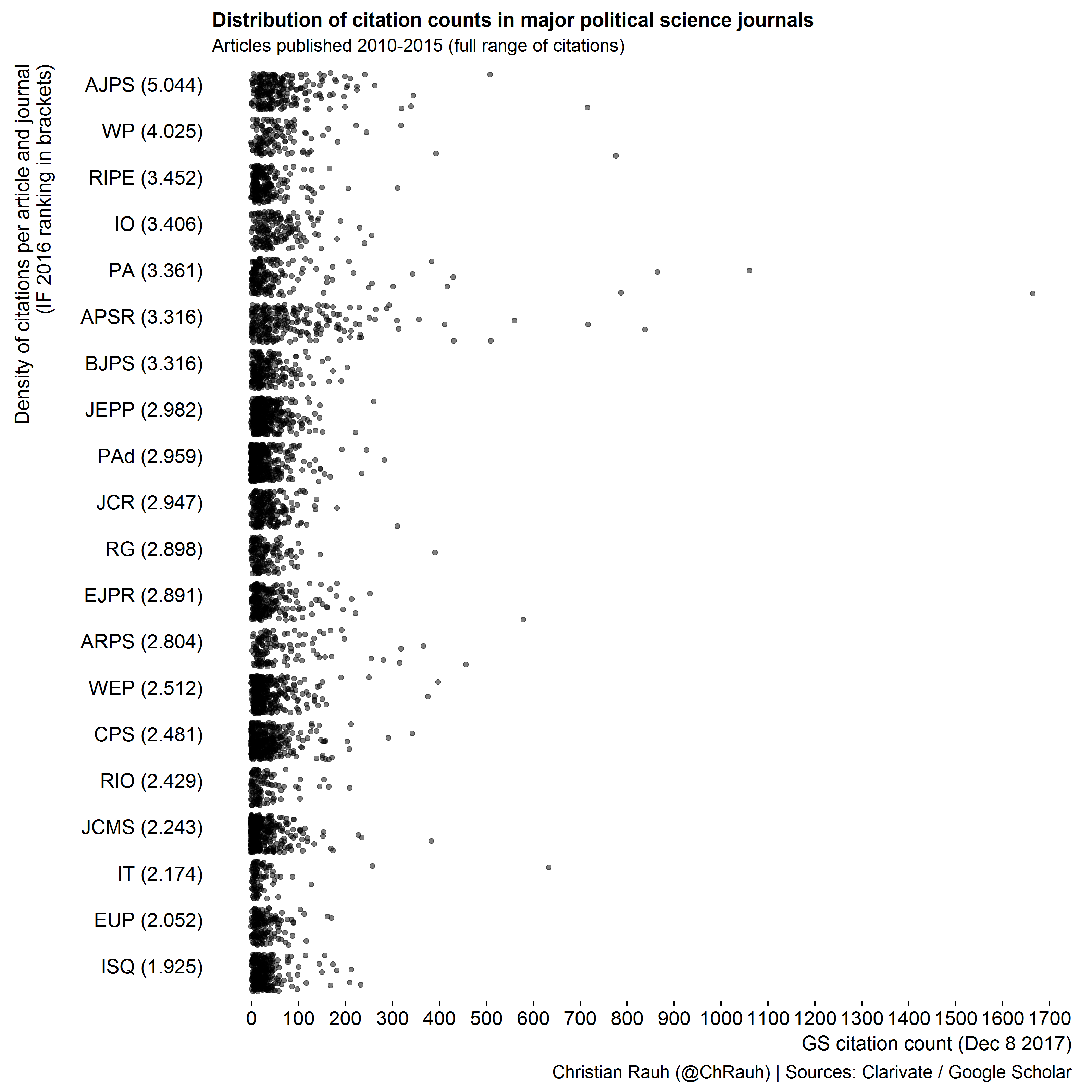

When preparing an upcoming group evaluation, I wanted to make these points clear for my team. I thus collected citation counts for all manuscripts published over the last five years in those political science journals that were considered as leading along their current 5-year impact factor. The plots below show this journal list in descending order of IF and illustrate the distribution of individual manuscripts’ citation counts as densities and jittered dot plots.

We clearly see that most journals – especially those at the top of the ranking - feature rare but strong outliers of highly cited manuscripts. Those affect the journal impact factors disproportionately which also means that they offer little information about most manuscripts in that journal.

We also see that the distributions are heavily right-skewed in most cases – the overarching majority of manuscripts receives much less citations than the what the average impact factor would suggest.

Moreover, the modes of the citation distributions across journals vary in a much narrower range than their averages. If we were to randomly pick two manuscripts from, say, the third-ranked journal and from the tenth-ranked journal, their citations counts would probably not be that different. Hardly a basis for distinguishing “top-top” from “top”, I’d say …

All of this suggests that there is no particularly strong relationship of a journal’s impact factor and the citation counts of individual manuscripts therein, as we also see below.

In short, the “top-top journal” heuristic seems to be rather flawed when it comes to inferring the (citation) impact of individual manuscripts (and their authors). Please avoid that simple shortcut when assessing the work of your peers.

Flipping the perspective

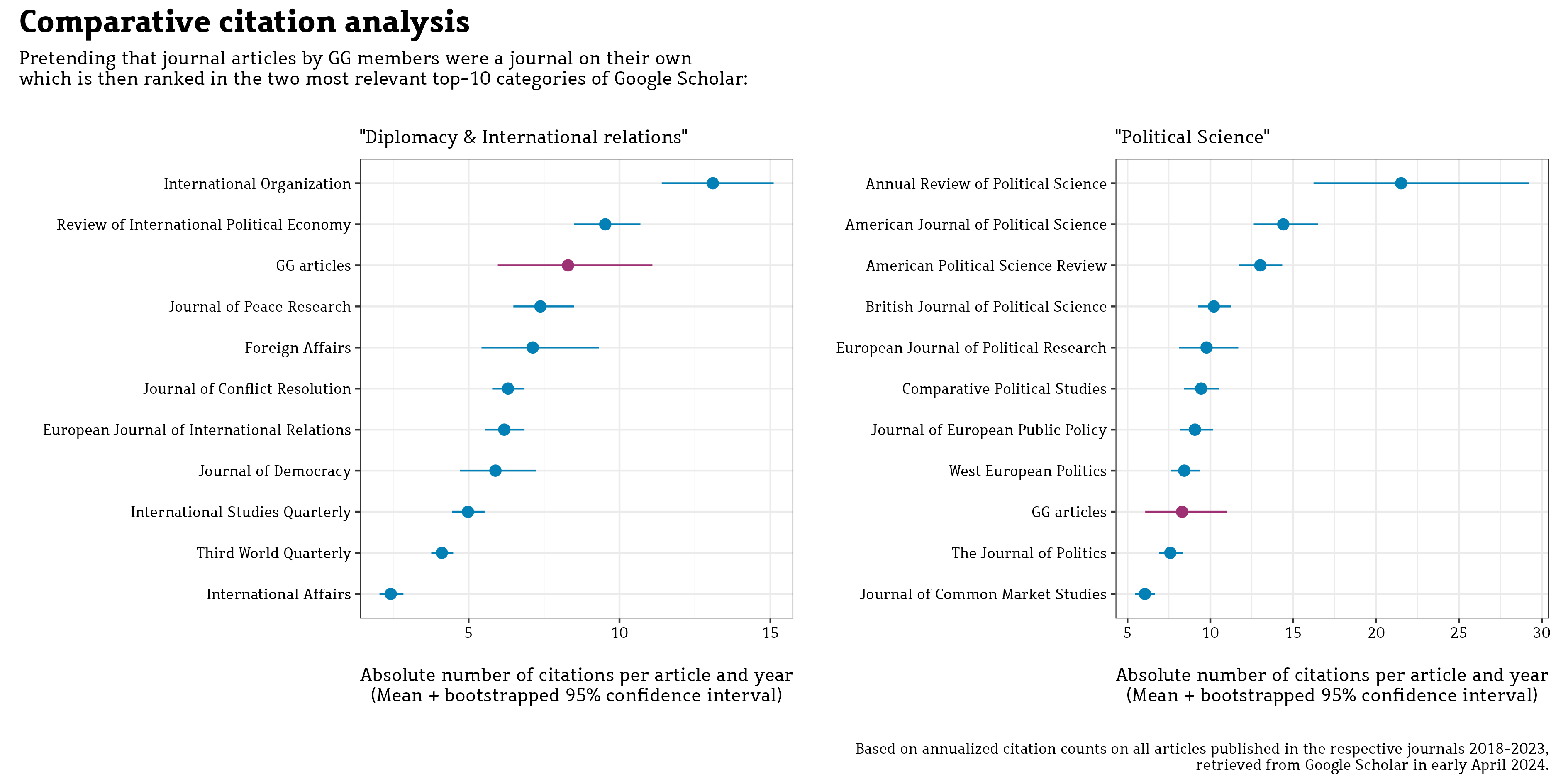

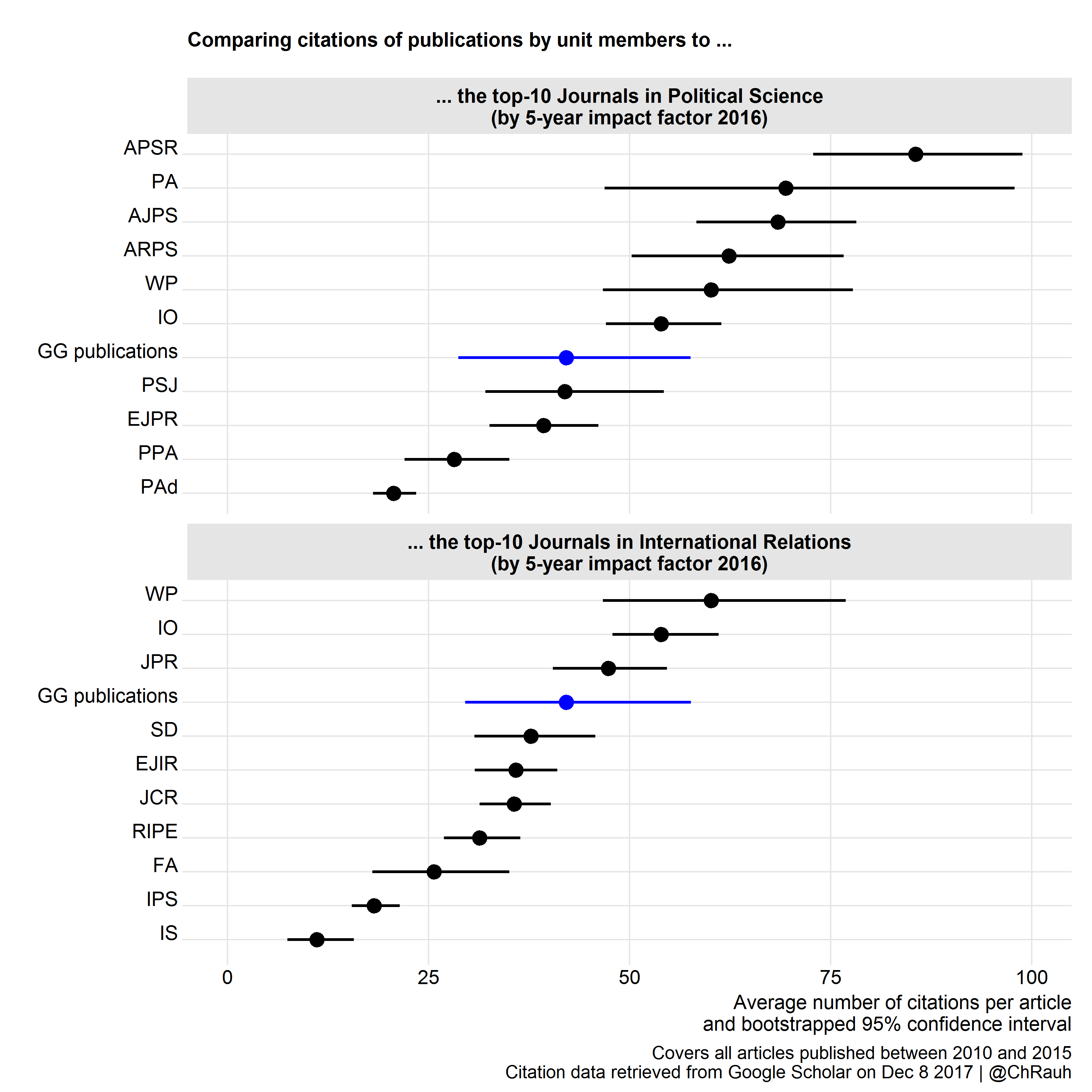

Of course, criticizing the evaluation criteria is hardly a winning strategy while you are being assessed. But to nevertheless preempt this overly simple heuristic in our particular case, I used the evaluation report to indirectly flag the idea that manuscripts make impact factors (and not the other way around). To this end I collected citation counts for all works published by our group in the evaluation period, pooled them into a fictitious journal, and then ranked this journal relative to the other journals in political science and international relations (resorting to Google Scholar data and classification schemes). That message was well received …

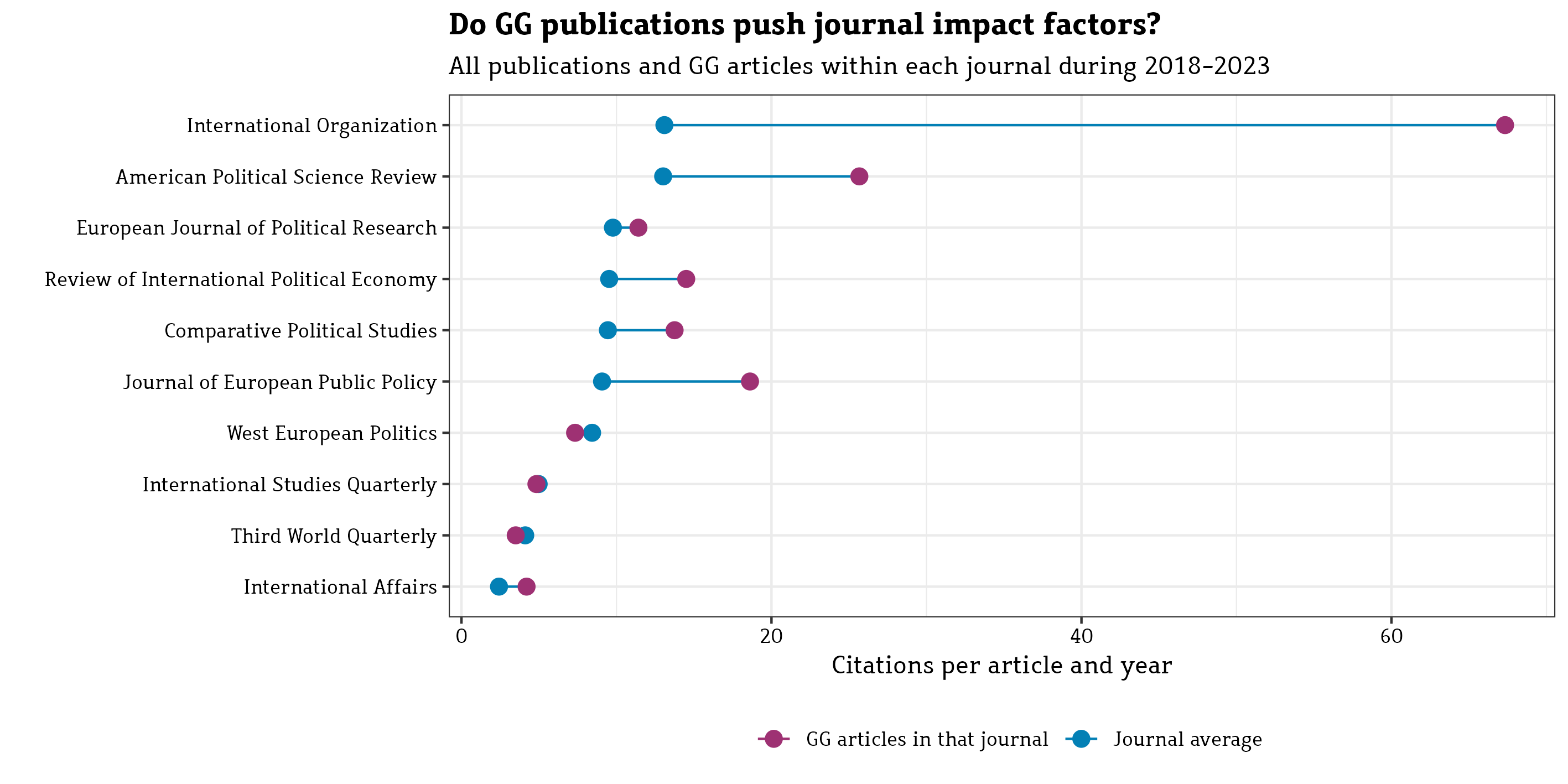

Update May 2024: In another evaluation I signed responsible for (sigh…), I pushed this idea further by also asking whether our publications actually have a positive effect on the impact factors of the journals that they appear in …